SHORTS: short stories and articles by Roderic…

Aside from his four published books - After The Flames , Sacred Tears , The Sullen Hills and The Governor's Lover - and working on his next full book, Roderic also writes occasional short stories. This is where you'll find them!

Roderic has written three short stories of his time as a United Nations Peace Keeping Officer in the Middle East : Climbing the Great Pyramids of Giza , Marooned in the Sinai and High-flying pranks over the desert sands

Read on, to read them…

Click below to jump to a story:

High-flying pranks over the desert sands

Climbing the Great Pyramid of Giza

Marooned in the Sinai

High-flying pranks over the desert sands

Following a decision by the Australian Government to provide helicopter support for the United Nations Emergency Force in Egypt, a contingent of Australian pilots and engineers operated four UH-1H Iroquois helicopters out of the El Gaala airfield in Ismailia. AUSTAIR's operational duties included patrolling the buffer zone and its boundaries and regular UN Military Observer (UNMO) changeover flights between Ismailia and checkpoints within the zone.

UNEF headquarters were located in Ismailia, a mostly destroyed and desolate town on the Egyptian side of the Suez Canal. Being strategically placed on the waterway that allowed shipping to cross from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, it had been the scene of heavy fighting during the Yom Kippur war between the Israelis and the Egyptians just a few years prior. The city was laid out in contemporary 19th-century style, with broad avenues, tree-lined squares, parks, and gardens, and had a gridiron street plan with a large number of destroyed and shell-pocked buildings, some dating from British and French involvement from when the canal was built.

Each of the four field contingents (SWEDBATT, GHANBATT, INDBATT, FINBATT) located in the buffer zone was allocated two air patrols weekly to inspect their boundaries and the area under their operational control. In addition, there were 'special' flights tasked to carry senior officials and contingent personnel on inspections or as required by HQ UNEF, and medical evacuation flights which could be called at anytime. Flight operations within the zone had to be cleared by both the Egyptian and Israeli military authorities, and they were usually flown at a low altitude to enable the UN military observers (UNMO) to get a better view of any tracks or strange markings in the sand.

As the Field Inventory officer responsible for the monitoring and contingent changeover of all UN equipment in the UNEF area of operation, I often used these AUSTAIR flights to conduct inspections in the remote regions of the buffer zone, some extremely hard to reach by vehicle. The time it usually takes to get down to the southernmost base which is the furthest away would involve crossing the Suez Canal on a military pontoon bridge which is setup at 6:00 am for an hour, traversing the Egyptian front lines through layers of minefields and rusted barbed wire fences into the buffer zone, and then driving on unpaved roads through the hot (45-50 degree centigrade) wind-blown desolate Sinai desert. This could typically be around 6-8 hours depending on conditions at the time.

I clearly remember the first time I went out on one of these air patrols. I was inspecting a Forward Logistic Base (FLB) located in Ras Sudr, a small settlement on the northern Red Sea, in the FINBATT area of operations. The two Australian pilots and their aircrew knew it was my first time in a helicopter and made sure I wouldn't forget the experience. On the outward leg, they flew fast and low over the dunes, swooping and rising over the sandy crests, which seemed just a few feet below the aircraft. When we got to the Israeli border fence line, it got much worse. The border wasn't a straight line on a map but randomly followed waves of sandy dunes, steep-walled wadis (seasonal watercourses), tall rocky outcrops and steep granite mountains in the south, all of which necessitated rapid changes in height, twists, turns, and high speeds in various directions. Even more disconcerting was a high-pitched alarm warbling from the cockpit that pierced your eardrums.

Later, when I inquired what the alarm was for, I was informed that the Israeli army liked to target the UN air patrol using their Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) radars to let them know that they were being monitored and not to cross the border into their territory. The high-pitched sound was a threat alarm, warning the pilots that they were being 'painted' by the Israeli radars. It was a cat-n-mouse game the pilots liked to play with the Israelis to keep themselves mentally sharp.

By the time we got to my destination, I was feeling dizzy and quite ill. It had been an hour of hell, feeling nauseous and constantly wanting to throw up! The Aussies were laughing when I staggered out of the helicopter into the arms of a Finnish logistics officer waiting for me to conduct my inventory. They took off after promising to pick me up on their way back to Ismailia later that day.

On firm ground, I immediately started feeling better. As the world stopped rotating around me, I consoled myself that the flight had saved me lots of time and that I would return to my apartment by evening. The last time I did this by vehicle, it took me two whole days to complete the task. Little did I know what the Aussies had planned for me on the way back.

After finishing the inventory to ensure that the UN equipment assigned to the FLB was not lost or stolen, I was back at the landing pad late afternoon, just in time to catch the flight back to Ismailia. It started pretty sedately. The crew had picked up a military observer, completed their air patrol, had refuelled at another FLB after dropping the UNMO off and was looking forward to returning to the airfield in Ismailia.

Flying back into Egypt from the buffer zone was not as easy as flying out. The Egyptian military allocated a 'window' for the helicopter to cross into their territory. The aircraft had to fly back at a specific time, at a precise heading, altitude and speed. This procedure was implemented as a safety measure to ensure the Egyptian SAM batteries wouldn't mistake the UN helicopter for an enemy aircraft on their radars.

Still inside the buffer zone, we arrived south of Ismailia, where we would cross into Egyptian territory, flying over the Great Bitter Lake, but we were 18 minutes too early to meet our entry window. I overheard the two pilots discussing practising some exercise over the headset I was using without entirely understanding what was being said. "Hold on tight" was something I did understand as I felt the helicopter rise swiftly into the air, which I later discovered was around 1,000 feet above ground level (AGL), and then, without any warning, the main rotor engine cut out.

If you've ever been on a roller coaster, you know the feeling of falling uncontrollably. This sensation is almost like your stomach is being pushed into your spine, adding intense excitement, anticipation, and even fear. You can feel yourself rising from the seat, and it's as though your insides are floating. Then, you wait until gravity catches up. And when it does - bam!!! Expecting the helicopter to crash heavily into the sand, I held on for dear life and was astonished when it gently touched down even though the main engine was turned off.

I found out later that the two pilots were required to practice an emergency manoeuvre called 'auto-rotation' several times a week. This manoeuvre kept the rotor blades spinning if there was a main engine failure, allowing it to 'cushion' the uncontrolled landing. The pilots needed a reflexive response to such a catastrophic event, so they practised it until it became automatic. Of course, they chose to do their four auto-rotations each while I hung on desperately to whatever I could at the helicopter's rear.

Later that evening, at the Sinai Palace Hotel, a dilapidated five-storey building used by the Australians as their quarters located in the outskirts of Ismailia, several rounds of drinks were shared by everyone as the story of my first experience of flying in a helicopter got taller by the telling. At the end of the night, I was finally initiated as an honorary Aussie by having to hang upside down from a beam over the roof side bar while skulling a pint of beer, which is an entirely different story.

'High-flying pranks over the desert sands'

All words and images © Roderic Grigson (2024). All Rights Reserved. No unauthorised reproduction permitted.

Climbing the Great Pyramid of Giza…

The sky to the east glowed from the lights of Cairo which filled the eastern horizon as far as the eye could see. The night sky behind the city was lightening with the false dawn. Tiny boats on the river Nile, some already underway before sunrise, crept along the wide river that disappeared into the darkness to the south…

In 1978 when I was living in Egypt working for the UN Emergency Force, I joined a group of colleagues who had negotiated with one of the local tourist guides to take us to the top of the tallest pyramid outside Cairo.

The Great Pyramid is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the suburb of Giza located to the south west of Cairo. It is the oldest of the seven wonders of the ancient world and the only one to remain largely intact. The pyramid was built around 2560 BC and was the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years.

We had heard from others who had climbed to the top of the great pyramid, that watching the sun rise over the city of Cairo was one of the great travel adventures in the world. Climbing the pyramids, although once a popular tourist activity, was considered extremely dangerous and was officially forbidden.

In the early evening, nervous with anticipation for what we had planned, we left Ismailia, a small city on the Suez Canal, to drive to Cairo. There were eight of us in two cars, four Brits, two Aussies, a Canadian and me. Tony, a Brit who had climbed the monument before, had volunteered to take us to the top. The real reason, I found out later, was that he was sweet on Wendy, one of the two Aussie girls who were accompanying us, and had offered to take her to the top to ‘see the sights’. I don’t think he was too happy when he found out that she had invited her friends along and that his little tête-à-tête had expanded exponentially.

The desert road between Ismailia and Cairo was straight and flat, the only danger being a stream of ‘flying coffins’ racing past. These Mercedes wagon taxis, filled to the brim with passengers, some sitting on one another, were driven at extremely high speeds which would be considered dangerous even on the immaculate autobahns of Germany. But here in Egypt, where fast, modern machines competed with centuries-old means of transport like donkeys and camels that wandered where they may, the clash of the ancient and modern was sudden and always catastrophic to both parties.

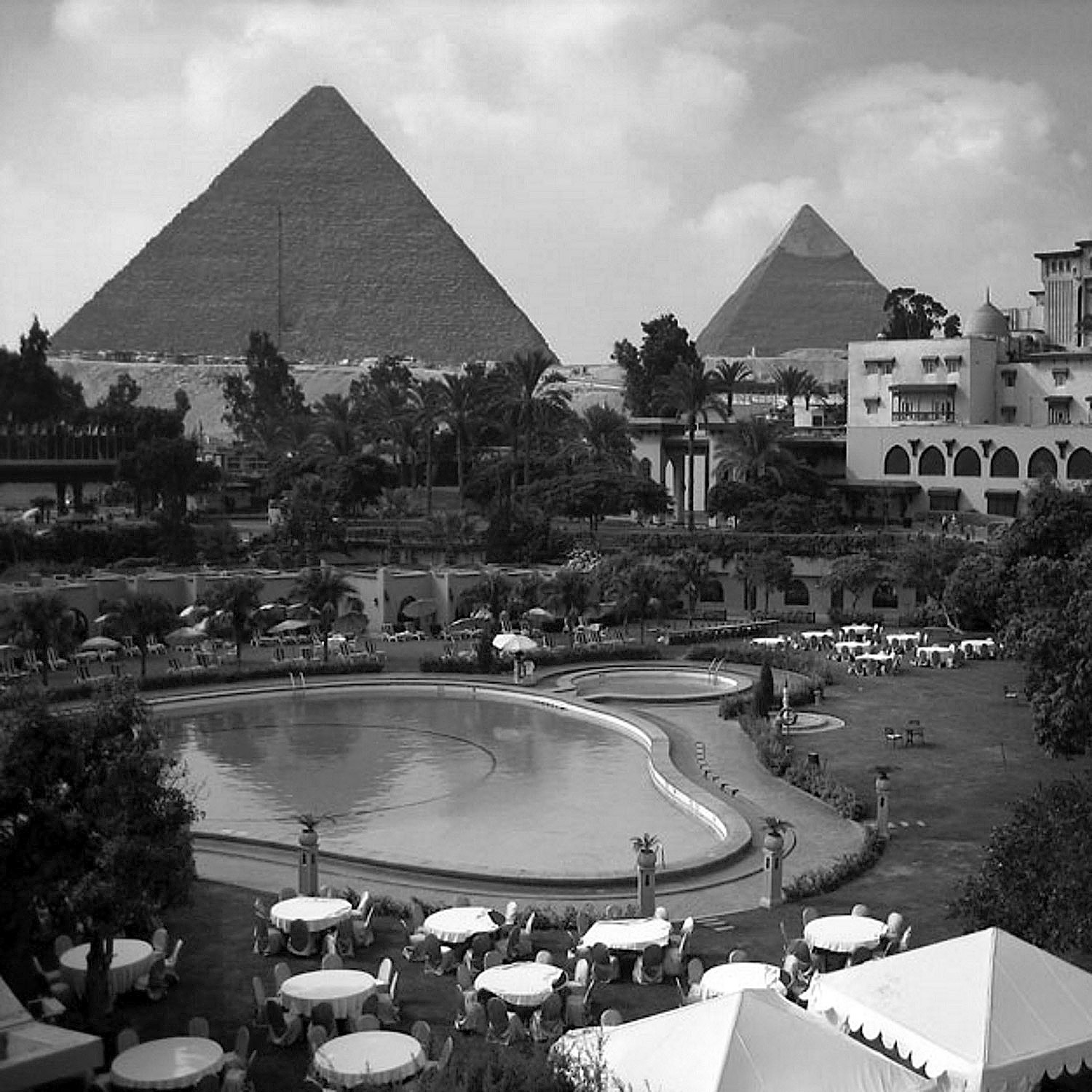

We arrived in the outskirts of Cairo after dark, passing through a checkpoint manned by Egyptian soldiers. Driving past the Cairo International Airport, we crossed the wide Nile River at the Giza Bridge before driving to the Mena House Hotel where we had reserved a few rooms for the night.

The Mena House was once a hunting lodge for the Khedive Isma'il (Isma'il Pasha, known as Isma'il the Magnificent was the Khedive or Viceroy of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879). The building was used by him when hunting in the surrounding desert or visiting the pyramids. It was opened as a hotel in 1886 and is one of the oldest and most unique hotels in Cairo.

Dinner at the hotel, located less than a kilometre from the pyramids, was loud and exhilarating. The pyramids which could be seen from where we were sitting, was lit up for the nightly Sound and Light show which bathed the structures in coloured lights. The excitement was palpable and most of us drank too much in anticipation of the adventure ahead of us.

We planned to leave the hotel after midnight so some of us took the opportunity to go to our rooms to rest in anticipation of the strenuous climb we had before us. I had heard that getting to the top of the pyramids was not for the faint-hearted. Some of the limestone blocks at the lower level were taller than the average human and I was smaller than an average human’s height.

We slipped out of the hotel in ones and twos. We had been warned that the hotel guards often stopped guests from going out at night on foot, demanding baksheesh to look the other way. We got past the guards without raising an alarm but the walk in the dark to the entrance of the pyramid precinct was far from unnoticeable. Word must have gotten out that a group of foreigners were climbing the pyramids that night and as we got closer to the gates, we seemed to attract a group of Egyptian locals like bees to honey.

The guards at the gate must have been surprised to see the approaching horde. Fortunately the guide with whom we had arranged the climb, had done his job. The guards manning the gates chased off all the touts, pimps and souvenir sellers allowing us to enter the enclosed area unhindered. Money changed hands and with broad smiles and pats on the back, we were asked by the guards to follow the guide who gestured us towards the base of the pyramid.

Even in the dark the Great Pyramid was an imposing sight. It towered over us, totally shutting off the night sky and stars from view. We were taken around to the eastern side, opposite the tomb of Queen Hetepheres, where we would begin our climb. The guide who could speak passable French, explained that it was easier to climb the side facing the city. The glow from the city’s lights would help us find our way up the 146 metre monolith.

Much to my delight, the first two levels of the pyramid were only shoulder high and most of us needed a boost to get to the flat surface at each level. But after the third level the blocks were only waist high making it much easier to negotiate. We didn’t climb up in a straight line however, the guide led us through crumbling gaps in the limestone blocks which allowed a much easier climb. One of the Brits whose name was Johnny and his Canadian friend Jim, decided to go straight up. I followed the two girls and the rest of the group who sedately followed the guide, mostly along one corner of the pyramid.

The limestone blocks were steep and crumbly. What looked like solid blocks of stone from the bottom were in fact covered with loose pebbles and sand. It was not easy to climb as our feet kept slipping out from under us and our hands kept losing their grip on the rock. What struck me as we were about halfway up was how cold it was getting. There was a light breeze which made it seem much colder. The change in temperature between day and night in the desert is quite significant and it felt much colder towards the top than it did at the bottom.

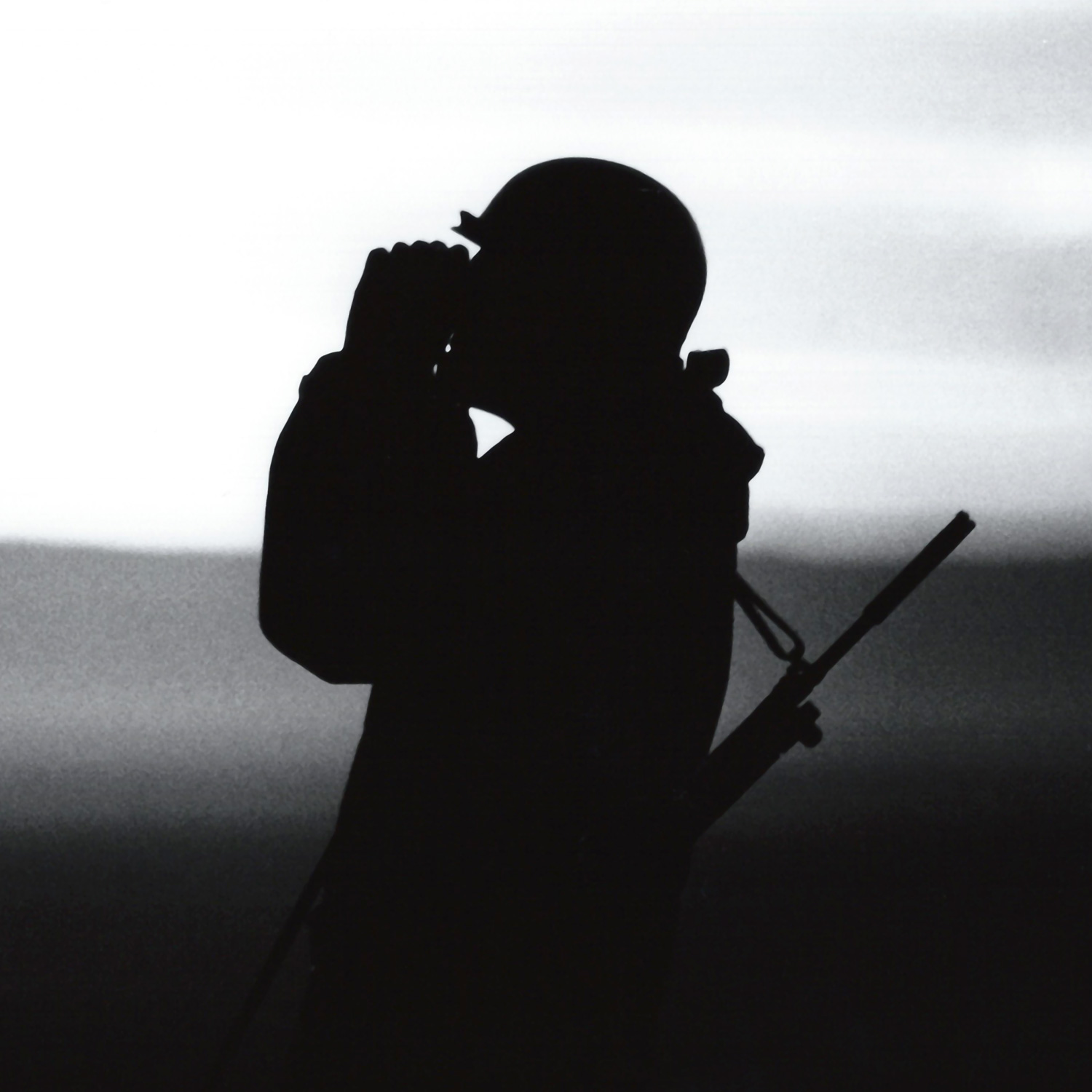

There was nowhere to rest as each ledge was only about two feet wide. We finally got to the top of the pyramid where I promptly sat on the ground. My legs trembled and my calves hurt from the exertion of climbing the limestone blocks. Jim, the Canadian who had rushed up the side of the pyramid with Johnny, had badly twisted his ankle and lay on the ground rubbing his leg in agony. Johnny who had brought a pair of binoculars with him, was looking through them towards the city.

The view from the top was spectacular. The lights of Cairo spread out to the north-east and the Nile River, looking like a black ribbon in the grey darkness, meandered sinuously towards the south.

The flat summit was bigger than I expected, perhaps the size of a very large living room. An old wooden post marked its center. We sat quietly, our feet dangling over the side, awed by what we could see. No one spoke louder than a whisper. Not that anyone could hear us but we were just overwhelmed by what we had done and what was spread out in front of us.

The enormity of the man-made structure was incredible. I had read at the hotel that the pyramid had been constructed of over 2.3 million limestone blocks and taken 20 years to build. The stones at the summit were worn smooth and I could see scratches and grooves cut into the rock from people who had been there before us.

Sunrise over Cairo was everything I had heard it would be. The normal pollution over Cairo had been blown away during the night and a thin sliver of light tinged with red and yellow suddenly appeared outlining the horizon which could not be seen in the dark. The sky got gradually lighter and red streaks mixed with pinks, yellows and blues reflecting off scattered clouds, gradually brought the city of Cairo into view. The sun peeked into view shining off the great walls of the Cairo Citadel, a medieval fortification built by Salah al-Din in 1183 to protect the city from the Crusaders. We had been warned not to bring cameras as the pyramid guards often confiscated them and sold them in the local souk. It was common practice amongst UN staff not to carry cameras around. Our job was to maintain a buffer zone between the Egyptian and Israeli forces and crossing the front lines was normal for us. The sight of a camera invariably meant being stopped and questioned and having the camera confiscated, and sometimes even being arrested for spying.

Ant-like figures in the pyramid precinct made me realise how high we were. To one side, a great sea of yellow sand stretched as far as the eye could see. On the other, a broad green belt with harvested fields and date palms surrounded the river Nile with the awakening city of Cairo on its banks. There was no sound to be heard except the undulating call to prayer from a mosque far below us.

The guide who had brought us to the summit started calling to us. He wanted to start the descent as he didn’t want to get caught climbing down. We waved off his pleas to leave wanting to spend more time enjoying the view. But as the sun rose it started to get hot and we reluctantly gathered ourselves to begin the descent.

Getting ready to climb down I could see graffiti dating back many centuries ground into the rocks at the summit. There were Greek, Latin, Arabic and other languages which I could not recognise plus those in English and other Western scripts. There were names of soldiers from the time of the French and British occupations with their regiments and years served carved into the rock.

Climbing down the face of the pyramid felt more dangerous than climbing up. We could now see how high we were and how dangerous it really was. Jim struggled coming down and had to be assisted by the rest of us who carried him from one level to the next.

We finally got to the bottom. It was only 8:00am but it was now really getting hot. We sat down talking excitedly amongst ourselves when we were startled to see a guard, shouting loudly in Arabic, rushing at us waving a pistol in the air. Our guide ran forward to meet him and a loud discussion with much hand waving took place. The guide came over and explained that the guard wanted to arrest us. Pulling a couple of us aside, he whispered knowingly that if we gave the guard some money he would go away quietly and ignore that we had just climbed down the pyramid.

Tony shrugged and handed a US$20 bill for the guard who immediately holstered his gun when he saw the money. The guard went off with a big grin on his face and I could not help but think that this was a well-rehearsed incident and we had just been suckered.

Walking back to the Mena House through an area of mud huts and wandering donkeys which looked like it had been there for centuries, I looked back up towards the summit feeling a sense of awe at what I had accomplished. A bit irresponsible and a bit dangerous no doubt, but I had done something that not many people had done. I had climbed the Great Pyramid of Giza!

'Climbing the Great Pyramid of Giza'

All words and images © Roderic Grigson (2017). All Rights Reserved. No unauthorised reproduction permitted.

Marooned in the Sinai

Egyptian soldiers manning strong-points along the Suez Canal started shouting in alarm. A siren wailed in the distance, and the dredges stopped working one by one. Floodlights along the canal winked out, a flare shot up high into the night sky, quickly followed by another, brightly illuminating the area we were in, in light and shadow. The misfiring engine, with its gunshot-like sounds, was creating pandemonium among the Egyptian soldiers positioned in the outposts between us and the canal. Below the crest of the dune, our jeep was totally invisible. A searchlight came to life, its long bright light probing the top of the dunes. A heavy machine gun thudded into action, its tracer-like bullets curving over us into the desert behind where we were hidden.

Being marooned and fired upon while negotiating a flood in the middle of the Sinai desert was no fun. And how did I find myself there? You may well ask. Well, here’s how!

My story begins in New York. I had arrived in the city as an innocent, idealistic youth of twenty-one, a tourist from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), the land of my birth. I had always wanted to experience the world outside my homeland that was undergoing the trauma of nationalism. It had recently gained independence from the British who ruled the island for 150 years. Being a Burgher, a descendant of the Portuguese, Dutch and British colonial rulers who governed the country for 450 years, our small community on the island was going through a period of disenfranchisement. This forced many of us to leave the country, seeking better prospects in places like Australia, UK, Canada and the US.

New York in the early 1970s was not the New York of today. It was a city compelling in its contradictions: a vibrant and very cheap place to live. It attracted talented young people from all over the world in droves. Known as the financial and entertainment capital of the world, it was also coming apart at the seams. ‘Stay away from New York City if you possibly can’ was the blunt warning that greeted visitors at New York city’s airports courtesy of a mysterious ‘survival guide’ with a hooded death’s head on the cover that symbolised one of the weirdest, most turbulent periods in the city’s history. Many of the warnings in the Fear City pamphlet were absurd exaggerations or outright lies. The streets of midtown Manhattan weren’t nearly deserted after six in the evening, and they were perfectly safe to walk on. There were still many safe and secure neighbourhoods outside Manhattan, and there was neither a spate of spectacular robberies nor deadly fires in hotels.

Yet, crime and violent crime had been increasing rapidly for years. The number of murders, car thefts and assaults in the city had more than doubled in the previous decade, rapes and burglaries had more than tripled, while robberies had gone up an astonishing tenfold. Vandalism was rampant, and many communities in each of the city’s boroughs were in advanced states of decay. There was also a pervasive sense that social order was breaking down.

Growing up in Colombo, the capital of Ceylon at the time, had prepared me for what I was about to face. Back at home, I had experienced first-hand, several communal riots and a vicious armed revolt conducted by a group of communist university students that was brutally suppressed by the government determined to ignore fundamental human rights. My being a pre-university student at the time of the insurrection was a definite hazard. At that time, it was safer for me to be out of the country.

After having been through all of that, New York, the Big Apple, even with its rotten core, didn’t seem such an awful place to be. Perhaps I was fortunate that because of my Burgher ancestry, I looked more like a Latino, a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American descent who made up a significant percentage of the city’s population, and was able to slip relatively unnoticed and untouched through the simmering cauldron that was New York City at the time.

Through a set of fortuitous circumstances, which is a story in itself, I was able to find permanent employment at the United Nations at its headquarters in New York. It was not a diplomatic post but a relatively obscure job in the Department of Conference Services as a documents officer. The organisation functioned in six languages, and my role as a part of a team was to ensure that everything was translated and published in all six regardless of what language the original was in. I was happy to be living in the US, working for a reputable international organisation on a semi-diplomatic visa, which allowed me to remain in the country as long as I worked for them.

Five years passed, and I was getting bored with the job I was doing at the UN. I had spent the preceding time wisely, studying the newly launched Computer Science courses at New York University, learned a new language (Spanish) and travelled whenever I could, visiting close relatives in England and backpacking across the US and Europe. I had quickly lost my idealistic view of life, having been tempered by the reality of living in the most dangerous city in the world, and I was ready to spread my wings. I was single and longing for some excitement in my life, so when the opportunity presented itself, I grabbed it with both hands.

In March 1978, after a massacre of its citizens on a northern coastal road by terrorists who came across the border from its neighbouring country, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) invaded Lebanon over its southern border to create a buffer zone and prevent further attacks on their border settlements. Lebanon at that time was a nation-state governed by different political and ethnic factions and militias, many who were intent on attacking Israel at every opportunity.

Following several late-night meetings, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) was created by the Security Council to keep the warring sides apart. As there was some urgency to have the UNIFIL deployed in South Lebanon, the UN called for volunteers amongst its permanent HQ staff around the world to serve with this newly created force which was forming in Israel.

Israel was a place I had always wanted to visit. As a student of history, my mind was filled with glorious stories of the birth and life of Christ, the Romans, the Saracens and their battles against the Crusaders, the vast Ottoman Empire and more recently, the creation of the state of Israel. I jumped at the opportunity to volunteer for a one-year assignment and found myself with only days left before I was to report to the northern Israeli seaside town of Nahariya near the Lebanese border.

The morning before I was scheduled to fly to Tel Aviv, I received a phone call from UN Field Services located on the 23rd floor of the UN building. It was the Duty Operations Officer.

‘Rod,’ she began. ‘I have some bad news. The Israelis are refusing to issue you a visa, and unfortunately, it’s going to take some time for us to get it sorted out.’

This caught me completely by surprise. It was not something I was expecting at all. ‘Why are the Israelis doing that?’ I asked curiously. The implication of what she was saying had not crossed my mind.

‘It’s because your country does not recognise Israel and has no relationship with them.’

Her statement made me think. I was born in Ceylon not long after it gained independence from the British in 1948. Both my parents were descended from British families who worked for the Crown in Ceylon, although I was considered a Burgher locally. I remembered that in 1967, after the Six-Day War between Israel and Egypt, the country which became Sri Lanka had spectacularly thrown out all Israeli embassy staff, severing diplomatic ties with that country and making headline news all around the world.

The pieces fell into place, and it began to make sense. This could be a real problem, I thought to myself. I carried a Sri Lankan passport even though I was eligible for British citizenship. I had been very much looking forward to going.

Unsettled by this development, I started thinking of various options to get around the problem. ‘Why do I have to go to Israel?’ I questioned the operations officer. ‘Isn’t UNIFIL based in Lebanon… why can’t I just fly into Lebanon?’

‘UNIFIL is being assembled in Israel because the situation in Lebanon has not stabilised, so you have to fly into Tel Aviv,’ she advised. ‘Anyway, it’s too dangerous to fly you into Beirut. The international airport is under intermittent mortar fire and has been shut down until the shelling stops.’

That made me pause. It looked like I had no choice but to go through Israel. ‘How long will it take to get the visa?’ I asked. ‘Is there a chance they will refuse again?’

‘There’s no guarantee they will say yes,’ the Operations Officer admitted. ‘It all depends. This has never happened before,’ she added. I could hear the sympathy in her voice.

‘Depends on what?’ I said anxiously, sensing her uncertainty. ‘You mean I may not be able to go at all?’

The days before my leaving had been filled with frenetic activity and a large wooden crate with my personal effects was already on its way to the middle east. The job I had been doing in the department of conference services had been assigned to someone else, and even though I was guaranteed a job when I returned to New York, everything would have to be rearranged.

‘If they refuse, yes!’ the officer said. ‘But we can get the office of the Secretary-General to intercede on your behalf.’

When she said that, I felt that the situation was getting completely out of hand. Why on earth would the Secretary-General (SG), the most senior diplomat in the United Nations, intercede on my behalf? With the thought of diplomatic cables flying between New York, Jerusalem and Colombo whirling in my mind, I thought that it was time to back off completely.

‘That sounds very complicated,’ I said nervously. ‘The SG must have more important things to do. Why don’t I just forget about going!’

‘No, no!’ the Operations Officer said firmly. ‘I am sorry if I gave you that impression. You’re a UN staff member travelling on a UN passport, and they can’t just refuse to grant you a visa because of your nationality. We can’t let them get away with that. You may not be able to travel tomorrow, but we will get you that visa, don’t worry. Let me talk to the Under-Secretary-General (USG) for Field Operations and get back to you in the morning.’

I hung up, wondering what would happen next. The head of Field Operations was General Brian Urquhart whose face appeared on the TV news almost daily. Getting the Israelis, the PLO and the various factions in Lebanon to allow a UN force to stop them killing each other was not an easy task it seemed. I went to bed that night quite despondent, not believing that the USG would have the time to take care of my insignificant little problem.

True to her word, the Operations officer contacted me first thing the next morning. ‘I’ve got good news and bad news,’ she said. ‘What do you want to hear first?’

‘The bad news,’ I said. I have always believed that getting the bad news out of the way first is better than the alternative.

‘Ok, you’re not going to UNIFIL,’ she said. My heart sank. That was bad news. ‘But don’t worry. We found you a posting in UNEF. We’ve booked you on a flight to Cairo, and you are departing from JFK this afternoon if you want it.’

That was the good news! The UN Emergency Force was a long-established peacekeeping operation between the Egyptians and the Israelis, and according to news reports, peace talks were about to get underway between the two countries.

‘Field services have made an official complaint to the Israelis through the SG,’ the operations officer continued. ‘You will serve with UNEF until the Israelis grant you the visa.’

‘Oh, okay,’ I said, feeling a bit better. It was not what I wanted, but going to Egypt was also a dream I had harboured for a long time. Visions of camels, the Suez Canal and the pyramids crossed my mind.

‘Good!’ the Operations officer said. ‘I’ll get the travel office to send down your passport with an Egyptian visa and the air ticket. Make sure you make the flight. You’ll be met in Cairo. Good luck!’

So, a few days later, after flying from New York to Rome and then on to Cairo, I found myself being driven across the northern desert to UNEF headquarters in Ismailia, a mostly destroyed and desolate town on the Egyptian side of the Suez Canal. Being strategically placed on the waterway that allowed shipping to cross from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, it had been the scene of heavy fighting during the Yom Kippur war between the Israelis and the Egyptians just a few years prior. The city was laid out in contemporary 19th-century style, with broad avenues, tree-lined squares, parks, and gardens, and had a gridiron street plan with a large number of destroyed and shell-pocked buildings, some dating from British and French involvement from when the canal was built.

I spent a couple of nights at a squalid local guesthouse, the only one in the entire town at the time, and after a few days, moved in with a Scottish Peace Keeping Officer (PCO) who was willing to rent out a room in his apartment.

Not long after my arrival in Egypt, I received a cable from New York saying that I had finally been granted permission to enter Israel. I was not told how it happened but happen it did. Unfortunately, the cable also said, that the original position I had been earmarked for in UNIFIL had been filled and I had to remain with the UNEF for the foreseeable future. This did not bother me as much as I thought it would as I had started to make friends in Ismailia and was beginning to enjoy living in Egypt.

Over the first month, I settled into my job as the Field Inventory Officer for the entire peacekeeping command, which was based in Egypt. The UN had millions of dollars’ worth of equipment spread across the whole region, and my job was to keep track of every piece of equipment worth over US$200. To do that I had to visit every single military observation post, checkpoint, platoon and company base, and battalion HQ in the buffer zone to physically view each piece of equipment. I was also responsible for managing the transfer of material between incoming and outgoing battalions every six months.

It was a physically demanding and dangerous job, and I had to be on the road all the time, crossing the front lines between the Egyptian and Israeli armies camped in the Sinai Peninsula. There was a ceasefire in place, but the two forces were still technically at war, and both sides were very edgy. The Israelis had surrounded the 3rd Egyptian army in the Sinai at the end of the fighting, and the only way they could be supplied was by sending food and water in trucks across the Suez Canal. The UN forces occupied a demilitarised buffer zone between the two armies and monitored areas of limited troops and weapons on both sides of the territory.

Needless to say, I looked for the first opportunity that came up to visit Israel. I found out that UNEF staff regularly drove into Israel from Egypt, especially on the weekends, and some even had apartments in Jerusalem where their families lived. There was a strict rule that UN staff could only travel across the front lines and into the UN buffer zone in pairs so I asked around whether I could join up with someone heading into Israel for the weekend.

My first trip into Israel turned out to be a truly memorable one.

My Scottish roommate was planning to spend a long weekend in Jerusalem and was happy for me to join him, as he too was looking for someone to travel with. His name was David, and he had been a UN Peace Keeping Officer for many years.

We checked out a white, UN-marked Jeep Cherokee from the UN transport garage in Ismailia on the following Friday and crossed the Suez Canal on a pontoon bridge which the Egyptian military erected twice a day. The pontoon bridge went across for an hour around midday and again around midnight. The canal handled roughly an average of 70 ships of all types a day. Sea-going vessels using the canal generally sailed from south to north in the morning and then switched to sail from north to south during the next twelve-hour period. This gave the military a window of about an hour and a half at each changeover to transport troops and supplies across the waterway into the Sinai.

Crossing the Suez Canal, the Sinai desert and the front lines between the two forces into Israel the first time was an experience I will never forget. The border post leading into Israel was operated by hard-eyed Israeli soldiers who refused to let me enter the country without authorisation from their superiors in Jerusalem.

Here we go again, I thought to myself as the soldiers signalled for us to park by the barrier. It seemed I was the first Sri Lankan who had tried to enter Israel from Egypt, and they had no instructions on how to handle my situation. The officer in charge, a Lieutenant who spoke perfect English, could not tell me how long that authorisation would take. I explained that I had been given permission by the UN authorities in New York to enter the country and requested that I remain at the border post until the matter had been cleared. I had come this far and refused to back down.

I was able to persuade David to continue to Jerusalem without me, which he did reluctantly. He had reported my situation to UNEF HQ duty room on the radio and was given permission to leave me at the border and continue onto Jerusalem if he chose to. There was an established procedure the authorities followed in such cases and him staying with me would not change anything. We were informed that my situation would be reported to UN HQ in New York and be closely monitored by UNEF Command.

After sitting around at the outpost for about three hours, the authorisation finally came through. I could only imagine what had transpired behind the scenes to make it happen.

I had spent the time waiting to make friends with the Israeli soldiers who were quite bored and found me a distraction. A couple of them had gone to school in New York, which gave us something to talk about. I found out from them that there were always taxi’s dropping people off at the border and that I should have no problem getting to Jerusalem if I was allowed into the country.

They were right. I was able to hire a Palestinian taxi driver whom I paid an exorbitant sum of money to drive me to Beersheba, a provincial capital about 50 miles away in the Negev desert. From there I took the regular bus service which ran from Eilat on the Red Sea, to Jerusalem, and hooked up with a relieved David at the hotel around midnight.

Jerusalem was everything I thought it would be. It was the fulfilment of a dream I always had, and all the difficulties I had faced trying to get here were just a memory. After a few drinks, we went straight to bed at the small hotel that UNEF staff used outside the old walled city.

Next day was Sabbath Day in Israel, and I spent all day exploring one of the oldest cities in the world. During its long history, Jerusalem has been destroyed at least twice, besieged 23 times, captured and recaptured 44 times, and attacked 52 times. It is the home to holy sites for Christians, Jews and Muslims, therefore significant to over one-third of all people on earth. Serene, surreal and intense are all words which jump to mind when describing the one-square-kilometre walled area, which was the Old City. I visited the Via Dolorosa (Way of Christ) and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre where Christ is buried, something I had always wanted to do.

That night I wandered through this amazing place, visiting the famous Arab souk, the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock. The souk is a Jerusalem landmark, the mercantile heart of this ancient city from at least Ottoman times to the present. The high arches and ceilings of the souk are a result of the same Ottoman generosity that gave the Old City its current walls, and no matter how many tourists are present, one gets the impression that the rhythms of the souk have remained the same for hundreds of years.

On Sunday morning, I walked on the ramparts around the old city, exploring its 4,000year-old history from above. The tiny, ancient walled city divided into an Armenian quarter, a Jewish quarter, a Christian quarter and an Arab quarter, is still the most fascinating place I have ever visited. The north sidewalk passes over the Christian Quarter with the numerous churches and other Vatican buildings seen, sometimes right below the wall! From the wall, you can see the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Church of Flagellation and many others. The walk carries on into the Muslim Quarter, where mosques and minarets, as well as schools and playing fields, can be seen. Crossing over the New Gate, the Damascus Gate, the Herod’s Gate and finally the Lions Gate, you pass by the Tower of David and cross over the Zion Gate. The walk covers the Armenian Quarter and ends at the Jewish Quarter, before the Dung Gate.

David, who was doing his own thing, met me for lunch at the Jaffa Gate, one of the main entrances to the walled city. After lunch, David was driving me down to see the Dead Sea when the ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio squawked into life. Every UN vehicle carried a military band radio which allowed all UNEF field staff to keep in touch with the radio room in UNEF headquarters back in Ismailia. We had to report in every few hours so that field operations would know precisely where we were. We were informed on the radio that Egypt was going to lock down their borders the next day and all UNEF field staff in Israel were ordered to return to base immediately. According to the report that was read out to us, Egypt was playing hardball with the Israelis in the Security Council before peace talks getting underway, and the UN were stuck in the middle.

This was going to be a significant problem for us. Monday was a public holiday back in Egypt, we planned to leave Jerusalem early in the morning and cross the canal on the military bridge erected in the early afternoon. Special permission in the form of an official travel document was needed to cross the Egyptian front lines after dark, and the only place we could get that pass was back in Egypt.

I was quite concerned by the situation we found ourselves in. Having already experienced problems with the Israeli authorities back in New York and at the border, I didn’t want to rock the boat in any way and overstay my first entry permit which was issued for only a few days. Having already experienced some of the wonders of Jerusalem, I didn’t want anything to ruin my chances of coming back into the country.

David did not seem to be concerned about what was happening. He told me not to worry, saying that he knew of a way we could get across into Egypt without an official pass. So, with his reassurances ringing in my sceptical ears, we set off from Jerusalem early that Sunday afternoon to drive back across the Sinai Peninsula to Ismailia. We drove south, stopping briefly at a second-hand bookshop in the outskirts of Jerusalem, where David rushed in and bought some books and magazines to take back into Egypt.

We drove down the coast road, past the Palestinian refugee camps at Gaza and came to the Israeli border post near El Arish as the sun was setting. The Israelis, always businesslike and efficient, checked our UN IDs and passports and let us through without any problem.

We drove to the UN post leading into the buffer zone, which was operated by Swedish troops. David knew the Officer-In-Charge; a Captain, who was on duty at the time. The camp was located by the road, and the Officer invited us into a tent to have dinner with him and his men. The meal comprised of steaming hot potato soup and slices of black bread, which I looked at suspiciously.

Was that old bread? I had never seen anything like it before. But the others were digging in, so I took a tentative bite and dipped it into the potato soup which made it a little bit more palatable. Coming from a country like Sri Lanka, where all the food was spicy and delicious, I had never eaten anything like this before.

We finished our meal, and it was well after dark when we finally left the camp. Driving through the desert at night was like nothing I had ever experienced before. The sky was filled with stars. I had never seen so many in my life. Living in a big city does not allow you to see many of the distant stars and galaxies. The total darkness of the desert, without any ambient light, made much more visible. We drove through the UN buffer zone in the dark, following the narrow, tarred road shining in our headlights. After about an hour, we came to the UN checkpoint which restricted access into the buffer zone controlled by the Egyptian army.

Driving into the Egyptian controlled portion of Sinai was much more dangerous. We had to first negotiate an extensive minefield. We slowly zigzagged through the unmarked field, following the tyre tracks of vehicles that had preceded us. The wind was whipping up the sand in gusts and swirls exposing anti-tank mines as large as dinner plates on either side of us.

After about 20 minutes of driving through the minefields, we came to an Egyptian checkpoint, which was just a ramshackle wooden hut by the side of the road. A broken wooden pole-sitting on two barrels across the sandy road impeded any further progress. A single bulb hanging from a wooden pole glowed dimly illuminating an Egyptian soldier manning the barrier. The young soldier walked over to where we were stopped. He was unshaven, his uniform crumpled and dirty like he had been sleeping in it. He carried an AK-47 automatic rifle on his shoulder. I noticed that the barrel had been painted in blood red. Not standard issue, I thought to myself.

The soldier put out his hand to David, who wound down the car window. The rumble of a generator somewhere out of sight was the only sound that could be heard.

‘Pass?’ He grunted, peering into the vehicle. He looked irritated and tired; the odour of his unwashed body permeated the jeep, making me gag involuntarily.

David handed our two UN IDs to the soldier. The soldier looked at them briefly and gave them back. ‘Pass?’ he grunted again, in heavily accented English, wagging his hand.

‘Mafeesh,’ David said in Arabic, shaking his head. In the short time I had been in Egypt, I had learnt a few words of Arabic, but ‘mafeesh’ was beyond my comprehension.

The soldier scowled at David, shifted his eyes to me and then straightened his back. He turned towards the hut and shouted something loudly in Arabic. A short, curt answer in the same language was shouted back at him from inside the hut.

The soldier motioned to David to park the vehicle by the side of the road and returned to his post behind the barrier, tiredly leaning against the wooden shack.

‘What did you tell him?’ I asked David nervously. ‘He’s not going to let us through.’

David looked at me. ‘I told him that I have nothing more to give him.’ David turned off the jeep engine. ‘Don’t worry, I have a plan. We’ll get through.’

Picking up the radio handset, David called in our current situation to the duty officer in Ismailia. The duty room was staffed 24 hours a day, and everyone in the field was tracked and monitored at all times of the day and night. After he finished his report, David started rummaging in the seat behind him.

Not confident of David’s ability to get us past the border post, I was fully expecting to wait the night out in the jeep. With my fear of overstaying my travel permit somewhat allayed by crossing the border out of Israel, I tried to make myself comfortable by pushing the back of the seat into a reclining position so I could get some sleep.

David turned on the inside light of the vehicle and pulled out a magazine from the bag he dragged out from behind his seat. It was an old, Playboy magazine. He leafed through the tattered magazine, pulling out the centrefold picture, turning it around and looking at it from different angles.

Suddenly, the vehicle shifted as if something was pushing against it. I felt the presence of faces pressing against the windows. Other soldiers at the checkpoint had appeared from nowhere. They had all left their posts and were crowding around the jeep looking in excitedly. David was having a great time, turning the magazine this way and that so that the soldiers would only get tantalising glimpses of the centrefold model.

Soon there was a knock on the window and a Sergeant, identified by the strips on his uniform and clearly, the person in charge of the checkpoint, gestured to David, motioning him to open the window. David shook his head. The Sergeant kept knocking on the glass insistently, so David wound down the car window halfway.

‘Whad’ya want?’ he asked the Sergeant rudely, closing the magazine as he spoke.

‘Want book us,’ the Sergeant replied in broken English, pointing at the magazine.

David shook his head, putting the magazine on the floorboard beside him. ‘No, I cannot give you the magazine. It’s mine.’

‘Yes, yes! Please give magazine. We want,’ the Sergeant insisted.

David shook his head, emphatically. ‘You are not my friend, so I cannot give you the magazine.’ David looked across at me and smiled. I sat up straighter in my seat, this was beginning to look fascinating.

The Sergeant was getting agitated. The soldiers were all talking to him at the same time, and he shouted at them until they quietened. He looked impatiently at David. ‘Yes! We are your friend. Give magazine.’

David responded calmly. ‘No,’ he said, shrugging his shoulders, ‘you won’t let me go home, so you are not my friend.’

The Sergeant shook his head. ‘Cannot go home without pass. But I am still your friend. You can stay here until morning. No problem!’

David reached into the bag and pulled out two more Playboy magazines. Loud bursts of Arabic directed at the Sergeant from the other soldiers looking in made him hesitate. He shouted angrily back at them, and a loud argument broke out.

After a lot of shouting and hand waving, the Sergeant looked back at David. ‘Okay,’ he said resignedly. ‘If you give magazine, you can go home.’

David winked at me and let the Sergeant have the magazines through the half-opened window. The Sergeant grabbed the three magazines and walked to the hut surrounded by the soldiers who were trying to seize the magazines from him. Before he went into the building, he shouted at one the soldiers, pointing to the barrier. The soldier ran to the wooden barrier, knocking it over before rushing back to the shack.

Using the radio, David reported to UNEF HQ in Ismailia that we were crossing into Egyptian territory, which was Standard Operating Procedure and was expecting to cross the canal around midnight. He was laughing as we drove over the broken wooden pole. ‘We always keep a few girly magazines in the car for the soldiers,’ he said. ‘You can’t get them in Egypt, and they are worth their weight in gold.’

I could not believe what I had just witnessed. We had just crossed the frontlines of a country that was still in an official state of war with its neighbour, using a Playboy magazine to bribe our way through! And without any record of us ever being there. To be perfectly honest, I was petrified that the soldiers would just shoot us and take the magazines. They could quickly have buried us and the jeep in one of the sand dunes, and no one would ever have known where we were.

As we drove further and further away from the border post, I settled myself comfortably into the seat, knowing that we were almost home. David was in good spirits, loudly singing a song in Gaelic as we drove down the road.

I wouldn’t have felt so relaxed if I had known that the adventure was not yet over.

We continued down the sandy desert road towards the Suez Canal trying to avoid deep, unfilled shell holes from when the Israelis counterattacked and pushed the Egyptians back during the war.

It was close to midnight when we saw the lights of the canal ahead of us. Large cargo ships brightly lit up for the night were sailing from the right to the left of us. We could not see over the dunes, so it looked like the ships, each framed by thousands of bright stars, were sailing across the desert sands. It was quite a spectacular sight.

When we got closer to the canal, the road dipped into a lower section of the desert. As we drove down the road, we could see that it was completely filled with water. The Egyptians were widening the canal so that ships could pass in both directions at the same time. The water came from three dredging barges that were blasting the side of the narrow waterway with water cannons to widen the waterway. The watery sludge was sucked up and flung hundreds of feet into the air by gigantic hoses pointed into the desert.

‘What should we do?’ I asked David who stopped the jeep just short of the water.

‘We have to keep going,’ he shrugged. ‘We don’t have a choice. The pontoon bridge will go up in the next half-an-hour or so and we’ll only have an hour to get across the canal before they dismantle it.’ He looked across at me. ‘If we don’t try, we won’t get to Ismailia by morning.’

I nodded my acquiescence and David drove into the water slowly, following the road which we could see emerging from the oily water about 300 metres away. The water was dark and stank of diesel. David sped up as we got close to the other side when suddenly, we drove into a large shell hole concealed by the water. Water splashed up, and the engine coughed and stalled. We were right in the middle of the shell hole; water washing over the floorboards of the jeep was rising rapidly. David swore in his inimitably Scottish way and tried starting the vehicle, but it would not start. The engine kept misfiring and would not catch.

The floodwater was still rising, so we got out of the vehicle into the flooded road, the water coming up to our thighs. With great difficulty, we dragged the jeep out of the shell hole and pushed it slowly onto the road, out of the water.

We were on dry land but just barely out of the flooded portion of the road. We did not have the energy to push the jeep up the incline to the top of the small dune, which I could see was entirely surrounded by water.

We’re marooned on a tiny island in the middle of the Sinai desert! The absurdity of our predicament did not escape me. I wouldn’t have believed it possible even in my wildest dreams.

The pounding of the dredges as they kept pouring the watery sludge into the desert was making it difficult to think straight. I tapped David on his shoulder and pointed to the water levels on the road, which were rising gradually.

‘We better get out of here quickly,’ I said. David opened the bonnet of the jeep and had a look inside, but without proper light, we couldn’t see much. He removed the distributor cap, cleaning it mostly by touch with a dirty rag before reconnecting it.

David tried to start the engine again, but it kept misfiring, water spitting out of the exhaust pipe explosively. He didn’t give up, trying to get the starter motor to turn over but as the engine dried out the sound of the misfires got louder and louder, sounding like gunshots over the pounding of the dredges.

Oh shit, this is not good, I thought to myself. Once the machine gun started firing, I knew we were in trouble. David stopped trying to start the vehicle, and we huddled in the jeep.

I hope they won’t shell the area. I must have said it aloud as David looked across at me. ‘No, they won’t,’ he said. ‘No heavy weapons are allowed into the buffer zone – it’s demilitarised.’ He had served with the British army before joining the UN and didn’t seem to be too concerned about what was happening.

My heart was thudding so loudly that it replaced the sound of the dredges that had suddenly stopped. Various thoughts ran through my mind. We had been instructed to always remain in the vehicle if we got into trouble or if there was a problem. The jeep was painted in white with large UN signs plastered on the rooftop, bonnet and sides and no one could mistake it for anything else.

The machine-gun fire was not slackening, and flares shot up into the sky every few minutes. Strangely, I was not panicking. I was scared and worried about the situation we were in but seeing how calm David was, I was somehow able to hold it together.

David looked across at me and shook his head in disgust. ‘Bloody amateurs,’ he muttered irritably. He reached across the dashboard and picked up the jeep radio handset.

‘UNEF 97 to UNEF Ismailia … UNEF 97 to UNEF Ismailia, Come in, please. Urgent assistance required. Over.’

After what seemed like a very long minute, ‘UNEF Ismailia to UNEF 97, Receiving Loud n Clear. State your situation. Over.’

It was the UNEF HQ duty room in Ismailia. David gave me the thumbs up and advised them that we had got stuck in the water being pumped out of the canal and that the Egyptians, mistaking the engine misfires as gunshots, were panicking and shooting at us. The Duty Officer told us that he would contact the Egyptian UN liaison officer right away and advise him of the situation. He ordered us to stop what we were doing and wait to hear back from him.

After what seemed like a long time, which I realised later was only about 30 minutes, the Egyptian soldiers settled down. They stopped firing their machine guns, not hearing ‘gunshots’ anymore but kept shooting flares up every few minutes to make sure that no one was sneaking upon them. We were in constant touch with the Duty Officer at UNEF HQ during this period, and once everything quietened, he advised us to remain in the vehicle. There was nothing they could do to help us given the current disposition of the Egyptian soldiers. He also informed us that he would arrange for a mechanic to be helicoptered to us at daybreak.

We remained in the jeep for the rest of the night, not able to sleep. Our clothes and shoes were soaked with water, and we reeked of diesel oil and other unknown fluids which had been pumped out of the canal. I was worried that an Egyptian patrol would sneak up on us and shoot us while we slept.

Sunrise was around 5:00am, and not long after, the distinct thumping sound of an Australian-operated UN helicopter heralded the arrival of a mechanic to get our vehicle started. The jeep engine had dried out overnight and given it was daylight, it didn’t take him long to get it started.

The next scheduled canal crossing was at midday which was 6-hours away, so we negotiated with the mechanic to drive the vehicle back to Ismailia while we flew back to base by helicopter.

I’d been in the country for only six weeks and had already experienced enough to last me a lifetime. I remember wondering at the time, What the next few months would bring?

'Marooned in the Sinai'

All words and images © Roderic Grigson (2017). All Rights Reserved. No unauthorised reproduction permitted.